The Nazi Party Rally

Grounds:

all that's left of the Thousand Year Reich

Copyright, January, 2003, All Rights Reserved

by William Cracraft

Nuremberg has worn many faces in its 950-year history, but few were as fleeting as the triumphant scowl of the Nazi party. National Socialist (Nazi or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler needed a base for his political assault on democratic Germany. Berlin was home to an entrenched bureaucracy and the Prussian military clique, and Munich was too sophisticated to rally early to Hitler's radical agenda, but Nuremberg, with its central location and conservative, more provincial population, was ripe for exploitation.

The old walled city had another important asset, a large plain

hard by, perfect for large assemblies, accessible by foot, auto and rail from

city environs and Germany at large. Known as Duzenteich, or Twelve Ponds, the

area was co-opted by the Nazis for their party rally grounds between 1928-38.

It has now returned to everyday use, the old monuments bleaching like old bones

in the sun.

The Timeline

Late 1800's: The 11-square-kilometer area is partially developed

as a recreation area.

1906: Bavarian Jubilee Exhibition held on the grounds.

1912: Nuremberg Zoo Opens

1923: 50,000 locals gather at Luitpold Grove, a quiet, woodsy

part of the park adjacent the city, in support of the democratic but doomed

Weimar Constitution. The first Nazi Rally is held in Munich.

1926: The second Nazi Party Rally is held in Weimar

1927: The third Nazi Party Rally is held in Nuremberg's Luitpold

Grove. All subsequent official rallies will be held in Nuremberg.

1928: City officials erected a monument to the dead of World War

I in the grove

1929: The fourth Nazi party rally is held. No rallies were held

the next few years as the Nazis consolidated political power by exploiting a

very poor economic situation.

1933: Hitler, already the German Chancellor, assumes the office

of President to become sole leader of the German government. That same year

he named Nuremberg the City of the Nazi Party Rallies.

1934: Building of the rally grounds begins in earnest when Hitler

anchors his Rally Grounds to the World War I monument in Luitpold Grove. The

Luitpold Arena was the first of seven monumental structures planned for the

Nazi Party Rally Grounds, called the Reichparteitagegelaende.

1933 through 1938, while construction was underway, six Nazi rallies were held on the grounds, each lasting eight days and attended by hundreds of thousands of participants. There were speeches by Hitler and other top Nazis, parades of all sorts, military demonstrations, propaganda displays, dancing exhibitions, fireworks and plenty of food.

The Monuments

At Hitler's behest, in 1934, Albert Speer (later tried in Nuremberg), and other architects laid out the monumental structures of the Nazi Party. Of the seven planned, one was never started, three remain and three have disappeared.

Lost Monuments

The Great Stadium, meant to be the largest in the world with a capacity of 400,000 people, was excavated, but work went no further. During the war, the hole filled with groundwater and the resulting lake is now known as Silbersee, or Silver Lake.

The Maerzfeld (Mars Field), a giant military parade ground, had 11 of 24 massive 130-foot tall towers built, but they were blown up in 1967 so the land could be developed. The Luitpold Arena, finished in 1934, had the Nazi additions, the tribune and Fuehrer's Walk, removed in 1959. The World War I memorial remains, a sudden stand of granite in a quiet park.

The Kulturhalle, to be used by Hitler for his speeches on cultural matters, never went past the planning stage. It was to be located at the northern end of the Grosse Strasse, opposite the Kongresshalle. That spot is now occupied by the local fairgrounds, where the city's annual harvest festival is held.

Finished Monuments

Two monuments were finished and retain a portion of their original grandeur.

The Grosse Strasse, or Great Road, a granite military

parade route two kilometers long and 60 meters wide, was finished in 1939. The

road, intended as the axis for the entire area, runs from the Kongresshalle

to where the Maerzfeld was to have been built. Made of 60,000 granite slabs,

it was used as an aircraft landing strip during the Allied occupation. Following

the war, as the city grew, the mighty Grosse Strasse, built to withstand the

simultaneous stomp of ten thousand gleaming jackboots and the tread of the fearsome

German panzers, became a convention center parking lot and a haven for skateboarders.

As a protected structure, parking is no longer allowed, but skaters, joggers

and remote control car aficionados bring life to the old Grosse Strasse every

day.

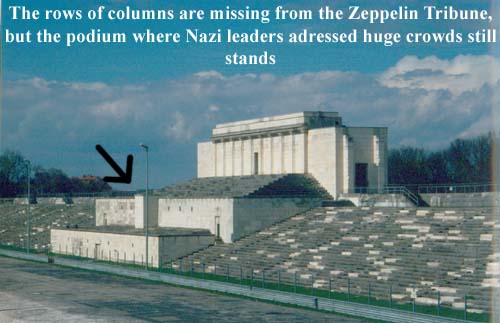

The Zeppelin complex, the centerpiece of the rally grounds, is essentially a great hollow square of granite risers, one side of which is the 300-foot long tribune, a grandstand with rostrum originally topped by rows of columns and flanked by huge torches. The complex was completed in 1937, and with room for 100,000 people, was the scene of the most lavish Nazi productions.

One of the best-known events at the Zeppelin Field took place in 1934, when Speer surrounded the field with 130 anti-aircraft searchlights pointing straight into the sky, creating what he called a Cathedral of Light. In 1945, following the end of the war, Allied soldiers dynamited the huge, gilded swastika mounted on the Zeppelin Tribune; the act was filmed and is often shown on television.

In

some sort of post-war karmic eye-gouge, both the Socialist Party, archenemies

of the Nazis, and the Jehovah Witnesses, who were savagely persecuted by the

Nazis, used the Zeppelin complex for mass rallies. The tribune's structurally

unsound columns were demolished in 1967, though rock performances ranging from

Bob Dylan to Metallica continued to be held on the field until 1998.

In

some sort of post-war karmic eye-gouge, both the Socialist Party, archenemies

of the Nazis, and the Jehovah Witnesses, who were savagely persecuted by the

Nazis, used the Zeppelin complex for mass rallies. The tribune's structurally

unsound columns were demolished in 1967, though rock performances ranging from

Bob Dylan to Metallica continued to be held on the field until 1998.

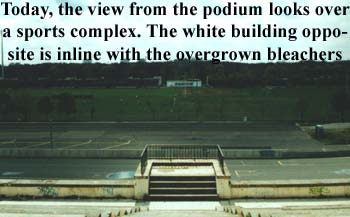

The area hosts the "200 Miles of Nuremberg" auto race every year, but mostly the field is used for track meets and local soccer games. The stone risers, eroded by a decade-old growth of brush and small trees, are barrows-in-training: soon they'll be completely covered in vegetation and become part of the landscape. In the early eighties, the Golden Hall inside the Zeppelin Tribune was restored and two massive Vietnam-era sculptures of shattered artillery barrels and other detritus of war were placed outside the oversized doors.

In 1985, forty years after World War II ended, a temporary, part-time exhibition called Fascination and Terror-Nuremberg and National Socialism opened in the hall. Open only during the summer, this exhibition was the pilot for the Documentation Center for the Nazi Party Rally Grounds.

Today, the tribune, once scrubbed and bannered, host to men who controlled the most feared army in the world, stands broken and deserted; the overgrown bleachers still paying homage to the cracked discolored rostrum where Hitler gave some of his most dramatic speeches.

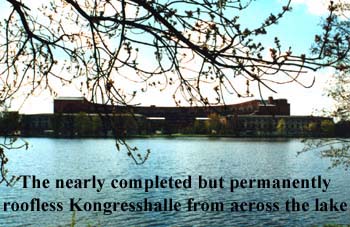

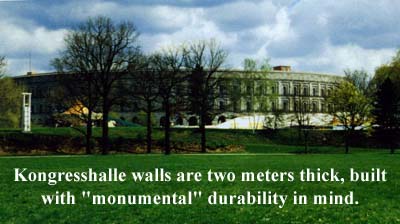

The Kongresshalle, last of the six structures, designed by architects

Ludwig and Franz Ruff, was nearly completed and remains standing. Ground was

broken in 1935 for the hall, a coliseum where party leaders 50,000 strong could

pay fealty to National Socialism.  The

imposing exterior of the Kongresshalle, a huge U-shaped brick structure with

a façade of granite arches, was completed, though no roof was ever raised and

interior walls remain bare brick.

The

imposing exterior of the Kongresshalle, a huge U-shaped brick structure with

a façade of granite arches, was completed, though no roof was ever raised and

interior walls remain bare brick.

Construction stopped during the war, and the structure, the largest remaining Nazi monumental building, was sealed up. In 1949, one wing was furbished up for the First German Construction Exhibition and in 1950 the City of Nuremberg used the wing in their 900th anniversary celebrations. Over the last few decades, the city used the small, finished portion for offices and leased the cavernous passages to Germany's giant mail-order retailer, Quelle, for warehouse space.

The main floor of the Kongresshalle became a courtyard occupied

by junked cars, tired machinery and stacks of old tires. In 1973 the Monumental

Style of the Third Reich was declared protected and the  City

of Nuremberg began long-term maintenance on all remaining monuments. No further

demolition was allowed and deteriorating monuments were attended to. A series

of 18-foot high kiosks explaining the origins of the structures and other facets

of the period were installed around the grounds.

City

of Nuremberg began long-term maintenance on all remaining monuments. No further

demolition was allowed and deteriorating monuments were attended to. A series

of 18-foot high kiosks explaining the origins of the structures and other facets

of the period were installed around the grounds.

Like the Zeppelin complex, the Kongresshalle remained in use. In 1997, brightly colored trucks were still trundling through its magnificent, shabby courtyard. By that time, the gears of German bureaucracy were in motion and the Kongresshalle was about to get new life as the Documentation Center for the Nazi Party Rally Grounds, a frank appraisal of Nuremberg's role in the rise of National Socialism and use of the rally grounds.

The Future of the Rally Grounds

Time and progress have taken a just toll on the old Nazi monuments, but change is slow, now. The Luitpold Arena has been neutered for forty years, and the Grosse Strasse, a broad strip of gray granite going nowhere was just restored. The Zeppelin Tribune, as the former high altar of Nazidom, is unlikely to ever see its soaring columns and great torches replaced.

On the other hand, Speer specifically designed the Zeppelin complex to age over hundreds of years, to leave ruins comparable to those of ancient Rome. In a moment of prescience in 1934, while designing the Zeppelin Tribune, Speer foresaw its deterioration. He prepared a drawing of what the tribune would look like after a few generations of neglect, its columns collapsed, grandstand covered with ivy. He presented his concept to Hitler: to construct all monumental structures in such a manner that they will last for hundreds of years even if completely neglected. Barring actual demolition, these structures are here for a long time.

The area as a whole will continue as a recreation grounds: using the structures as city furniture has de-sanctified the complex. Svenja Schmidbauer, 16, goes to the Rally Grounds to roller blade and play tennis. "I think it is good that we use the grounds for other things, because it shows we do not have respect for these buildings," she said.

As protected structures, the monuments will be maintained for safety purposes and their future re-assessed regularly. Perhaps some acceptable use will be found for the now-deserted Golden Hall. The overgrown Zeppelinfeld risers are deteriorating and may eventually be demolished, as restoration would be very expensive, said Hans Christian Taeubrich, director of the Documentation Center.

The Kongresshalle is a special case. Although it has been in regular use for a long time, and is now partially open to the public, "it has always been our intention to ensure that what Speer, the Ruffs and Hitler started would never be completed. Past ideas for converting it to a stadium or a leisure center were abandoned very quickly," Taeubrich said.

Limited development, however, is under consideration. Any new space used would need electricity, plumbing and heating installed, but "we are thinking of expanding (the center) and there are several very good ideas. I am optimistic that something will happen…within two to three years," said Taeubrich.

In the End

The Nazis developed the plain, and they have

left their mark, but ultimately, Nurembergers got their park back. Paddleboats

once again ply the lakes, countless thousands have partied at concerts on Zeppelin

Field and the Grosse Strasse is just a place where young people meet to rollerblade.